Table of contents:

The solution

A. Plan with accessibility in mind

Contrary to the belief that “accessibility is too costly”, one United Nations report affirms that “available evidence illustrates that urban infrastructures, facilities and services, if designed and built following accessibility or inclusive “universal design” principles from the initial stages of planning and design, bear almost no or only 1 per cent additional cost”.[1]

“Available evidence illustrates that urban infrastructures, facilities and services, if designed and built following accessibility or inclusive “universal design” principles from the initial stages of planning and design, bear almost no or only 1 per cent additional cost.”

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “Good Practices of Accessible Urban Development,” 2016.

If accessibility is put at the forefront of any development project or the construction of roads, transportation infrastructure, airports or other public and private facilities, it would save later costs to retrofit, adjust and revamp. This also includes basic facilities like residential buildings, schools, hospitals, police stations and emergency services, which provide critical services and need to be accessible.

B. Building back better in conflict and post-conflict contexts

Many conflict and post-conflict countries in the region – including Iraq ,Libya, Syria and Yemen for example – have an opportunity to mainstream accessibility in reconstruction and development efforts. Organizations of persons with disabilities in all those countries have been advocating for inclusive development in reconstruction efforts and could be an excellent source of information and support. This is especially the case when there are international agencies involved. The responsibility becomes heightened, as these organizations have access to the technical expertise that would facilitate mainstreaming accessibility.

This also applies in the case of reconstruction following emergencies and disasters, like the floods in the Sudan or the Beirut Port explosion, where rebuilding damaged areas presents an opportunity to make them accessible.

C. The business case for accessibility

The business case for accessibility can be best illustrated in the example of the tourism economy. Many coastal cities in the Arab region along the Mediterranean and Red Seas rely on tourism as the main economic activity.

“Taking accessibility into account in urban and rural development not only has tangible economic benefits, but it should be pursued as a goal in of itself, a human right enshrined in the CRPD with the consensus of the international community and its members.”

Making sure that hotels, beaches, restaurants and transportation are accessible would allow a greater number of tourists to visit, whether they are persons with disabilities, older persons, pregnant women, children and their caretakers. The same example applies across different economic sectors, with tangible economic benefits when facilities and services are made accessible.

Some inclusive design examples

- Coloured ramps: Very simply made and designed for places that are close to ground level, with one small step that is not accessible. They are light in weight, can be picked up easily with the ropes on the sides and help make facilities and businesses more accessible.

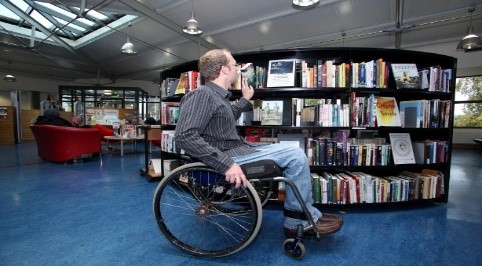

- More accessible libraries: The original design of libraries should be made accessible through a process of review and adjustments for existing.

- Two-level drinking fountains: for people of short stature, wheelchair users and children.

- Visual contrast: the use of bright colours for doors, walls, floors, etc allows persons with low vision to easily navigate and use the amenities.

- Accessible transportation: such as low-floor buses for wheelchair users.

[1] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “Good Practices of Accessible Urban Development”, 2016. Available at https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/desa/good_practices_in_accessible_urban_development_october2016.pdf.