Table of contents:

Profile of people with disabilities in Egypt

The research analysis draws on the WG disability measures introduced in the nationally representative data of ELMPS 2018,[1] executed by the Economic Research Forum (ERF) in cooperation with the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics of Egypt. Such measures are composed of six questions designed mainly to address different levels of difficulty in performing in six core functional domains. These domains are seeing, hearing, mobility, cognition (remembering and concentrating), self-care and communication. For each of these domains, the response difficulty categories are “No, no difficulty,” “some difficulty,” “a lot of difficulty,” and “cannot do it at all.” Difficulties in these domains within an inappropriate environment may be correlated with a greater risk of participation limitations. It is worth noting that this set of questions is currently the most used measure of disability worldwide (ESCWA, 2018). With a response rate of 82.7 per cent, the developed profile of people with disabilities depends on a sample of 50,634 individuals.

Following the WG (2020) guidance, three severity thresholds of disability are constructed. The first one is the “broad/any disability” threshold, in which any individual is considered to have a disability if he/she has at least a score of “some difficulty” in at least one of the six domains. The second measure is the “medium/severe disability” threshold, in which any individual is considered to have a disability if he/she has at least a score of “a lot of difficulty” in at least one of the six domains. Finally, the “narrow/complete disability” definition is the one in which any individual is considered to have a disability if he/she has a score “cannot do it at all” in at least one of the six domains. According to these three severity levels, the prevalence rate of disability is 16.6 per cent, 4.6 per cent and 0.9 per cent using the broad, medium and narrow definitions, respectively. Given the limited size of the sample falling within the narrow definition, most of the coming analysis is restricted to the broad and medium definitions.

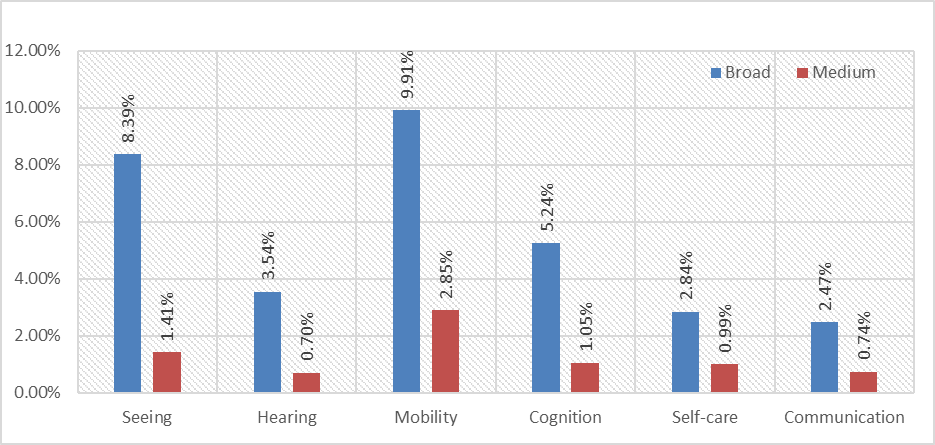

Figure 1 displays the prevalence rates of disability according to the six disability domains alongside the severity thresholds. As the figure shows, disability pertaining to mobility is the most prevalent type (9.91 per cent and 2.9 per cent), followed by seeing (8.38 per cent and 1.41 per cent) and then cognition (5.24 per cent and 1.05 per cent), using both broad and medium definitions, respectively. Communication is the least stated domain by the broad definition (2.47 per cent), while both hearing and communication are the least reported domains by the medium definition with very close rates (0.7per cent and 0.74 per cent, respectively).

Figure 1. Prevalence rates of disability by domains and levels of severity

Source: Based on authors’ calculations using ELMPS (2018).

It is widely agreed that disability intersects with many other socioeconomic dimensions that deepen and aggravate its influence on the quality of life. Such dimensions may include gender, age, region of residence, wealth and education. Accordingly, table 1 displays the prevalence rates of disability by the broad and medium definitions alongside those socioeconomic factors. Following in the strides made by El-Saadani and Metwally (2019), the associated odds ratios are further calculated to compare between different groups.

Starting with gender, the disability rates among females are higher than those among males under both definitions. Using the odds ratios, results show that females are significantly more likely to be persons with disabilities than males by the broad definition. However, this difference is insignificant under the medium definition.[2] Such a pattern may be due to what is called the health-survival paradox. This paradox states that females are more likely to live longer but have poorer health compared with males. Hence, they are more likely to acquire an impairment.

Moreover, the older the person, the greater likelihood of becoming a person with a disability, reflecting an accumulation of health risks across the lifetime. Disability rates rise remarkably with age and peak in the oldest age cohort (65+) under both definitions. Accordingly, the odds of having any or a severe disability increase while moving from the youngest cohort to the oldest one, and all are statistically significant.

As table 1 reveals, disability is greater in urban areas than rural ones under both definitions. Hence, compared with rural areas, the odds of having any and severe disabilities in urban areas are higher and statistically significant. One possible reason for such a difference is the older age profile of residents in urban areas (Krafft et al., 2019). Other possible reasons may be that persons with disabilities are more easily found and counted in urban than in rural areas. The analysis shows that such a higher rate of any and severe disability in urban areas stems predominantly from the main urban regions, namely Greater Cairo, Alexandria and the Suez Canal cities. Meanwhile, the disability rates in the urban lower and urban upper regions are very close to their corresponding rates in the rural lower and rural upper by both definitions.

The poverty-disability nexus is well established and confirmed throughout literature. Table 1 reveals that the rate of any and severe disabilities is the highest among individuals in the poorest quintile (Q1). Compared with this poorest group, being in the richest one significantly decreases the odds of having any and severe disabilities by 27 per cent and 48 per cent, respectively. These high rates of disability among the poor are expected since both poverty and disability reinforce each other.

Turning to education, the disability rate reaches its peak among the illiterate group by both definitions. The likelihood of having any or a severe disability decreases by 68 per cent and 78 per cent, respectively, in the tertiary education group compared with the illiterate one. What is especially striking is the slight increase in disability rate when moving from the secondary to tertiary category. Although this is a surprising result that requires more investigation, it was confirmed in the Egyptian literature, as in Sieverding and Hassan (2019).

|

|

Broad definition |

Medium definition |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Demographic and socioeconomic factors |

Percentage of persons with disabilities (Percentage) |

Odds ratios |

Percentage of persons with disabilities (Percentage) |

Odds ratios |

|

Overall |

16.6 |

-- |

4.6 |

-- |

|

Gender: Female Male |

|

|

|

|

|

17.58 |

(RG) |

5.04 |

(RG) |

|

|

15.6 |

0.9* |

4.15 |

0.93 |

|

|

Age groups: 0–11 12–19 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–64 65+ |

|

|

|

|

|

5.97 |

0.036* |

1.2 |

0.046* |

|

|

6.59 |

0.038* |

1.43 |

0.041* |

|

|

7.39 |

0.043* |

1.77 |

0.049* |

|

|

11.57 |

0.073* |

2.27 |

0.075* |

|

|

19.74 |

0.142* |

4.38 |

0.14* |

|

|

31.89 |

0.29* |

7.97 |

0.26* |

|

|

42.86 |

0.472* |

11.7 |

0.38* |

|

|

62.15 |

(RG) |

25.3 |

(RG) |

|

|

Geographical location: Urban Rural |

|

|

|

|

|

19.51 |

1.29* |

5.25 |

1.19* |

|

|

14.61 |

(RG) |

4.16 |

(RG) |

|

|

Wealth quintiles: Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 |

|

|

|

|

|

20.01 |

(RG) |

6.36 |

(RG) |

|

|

14.69 |

0.70* |

4.52 |

0.71* |

|

|

16.44 |

0.75* |

4.07 |

0.61* |

|

|

16.65 |

0.75* |

4.45 |

0.64* |

|

|

15.32 |

0.73* |

3.65 |

0.52* |

|

|

Education: Illiterate Reads and writes Primary Preparatory General secondary Vocational secondary Tertiary |

|

|

|

|

|

32.96 |

(RG) |

11.77 |

(RG) |

|

|

13.84 |

0.32* |

3.37 |

0.29* |

|

|

13.1 |

0.31* |

3.22 |

0.25* |

|

|

13.2 |

0.27* |

3.53 |

0.25* |

|

|

11.2 |

0.24* |

2.7 |

0.18* |

|

|

13.75 |

0.3* |

2.7 |

0.2* |

|

|

15.2 |

0.32* |

3.3 |

0.22* |

|

Source: Calculated by the authors using ELMPS (2018).

Note: Significant level: * P-value<0.001. RG refers to the reference group.

Moving to the situation of people with disabilities in the labour market, the sample is restricted to the working-age group (15–64) consisting of 35,401 individuals. For the employment status, we use the market definition of employment stated in the Nineteenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ILO, 2013), following Krafft et al. (2019). Within such a definition, search for an employment opportunity is required for the labour force and unemployment variables.[3]

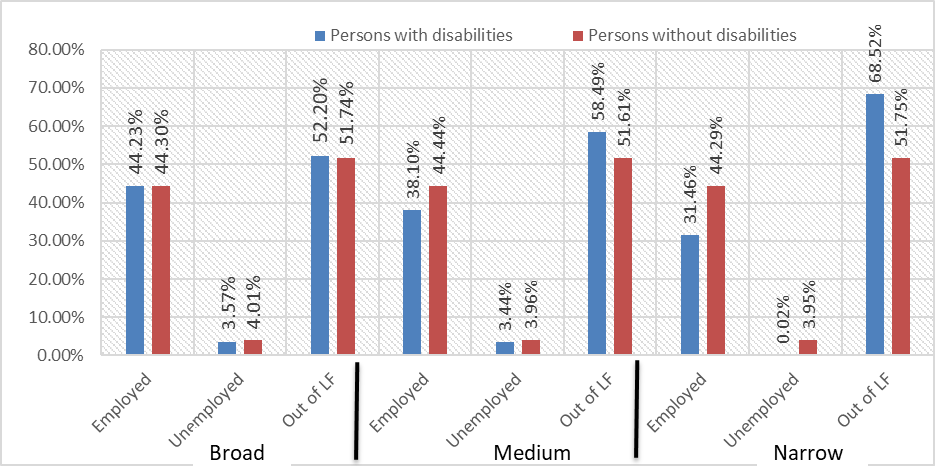

The prevalence rates of disability for the working-age population are 15.6 per cent, 3.7 per cent and 0.7 per cent by the broad, medium and narrow definitions, respectively. Starting with labour force participation and following the strides made by United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) (2019) and Sieverding and Hassan (2019), figure 2 displays the percentages of employed, unemployed and out of labour force among persons with and without disabilities, using the broad, medium and narrow definitions. As the figure displays, persons with disabilities across all severity levels tend to be out of the labour force. Generally, results reveal that while the overall employment-to-population ratio for persons without disabilities (44.3 per cent) is slightly higher than that of persons with disabilities (44.2 per cent) using the broad definition,[4] the employment gap between both groups is wider using the medium definition (44.4 per cent versus 38.1 per cent, respectively) and the narrow one (44.3 per cent versus 31.5 per cent, respectively).[5] The same patterns hold according to different socioeconomic factors, except in some cases that should be deeply elaborated, as shown in table 2.

Figure 2. Percentages of employed, unemployed and out of labour force by disability status and levels of severity

Source: Based on authors’ calculations using ELMPS (2018).

Disaggregating these rates by gender shows that the employment-to-population ratio of males without disabilities is higher than that of males with disabilities by the broad definition and considerably much higher by the medium one. One plausible explanation may be that having a disability is more likely to result in a disadvantage in finding employment, especially for males with severe disabilities. Interestingly, table 2 shows that the employment-to-population ratio of females with disabilities, as compared with males, is higher than that of those without disability using both definitions. This finding can be interpreted through their age profile in the Egyptian labour market. Employed females tend to be of older age (Krafft et al., 2019). Hence, they are more likely to be exposed to a disability if compared with the unemployed or out of labour force individuals, who tend to be younger. Such a result was further confirmed in the Egyptian literature, as in Sieverding and Hassan (2019). Examining these findings jointly reveals that being a male without disabilities guarantees a greater chance of employment. By contrast, females both with and without disabilities are less likely to be employed than males.

Regarding age, the employment-to-population ratio of people with disabilities (33.4 per cent) is higher than that of their peers without disabilities (28.9 per cent), in the two younger cohorts jointly by the broad definition. However, it is not the case for older cohorts. This result becomes clear if the association between disability and education is considered. In the two younger cohorts, approximately 19.3 per cent of persons with disabilities can at most read and write, compared with 11.2 per cent of persons without disabilities. On the other hand, around 43.8 per cent of persons with disabilities in these two younger cohorts are in secondary education or above, compared with 52.3 per cent of persons without disabilities. Accordingly, youth without disabilities in the younger cohorts tend to be in education, while their peers with disabilities are most probably out of education and engaged in some form of employment.

Notably, the employment-to-population ratio of persons with disabilities is higher than that of persons without disabilities in rural areas. Focusing on persons with disabilities, their employment-to-population ratio in rural areas is also higher than that of urban ones, using both definitions. These findings may be due to the fact that approximately 23 per cent of employees with disabilities work as unpaid family workers or are self-employed workers in agriculture. As for wealth quintiles, the employment-to-population ratio of individuals with any disability is the highest in the richest quintile. This result can be attributed to the fact that rich persons with disabilities can afford some kinds of employment (such as self-employment) compared with their poor counterparts.

The educational level of the individual with a disability plays a significant role in the employment of persons with disabilities. The employment-to-population ratio for persons with disabilities is the highest among people with tertiary education. Such a result highlights the importance of education on the likelihood of being employed. However, the fact that older people, who are highly concentrated in the lowest education categories, are more likely to be employed than younger people, makes the employment-to-population ratio higher within the first two categories than in the middle three ones. On the other hand, the employment-to-population ratio of persons with disabilities who have intermediate education or above is somewhat higher than that of their peers without disabilities. One explanation may be that once persons without disabilities are enrolled in education, they are more likely than persons with disabilities to continue education rather than engage in employment.

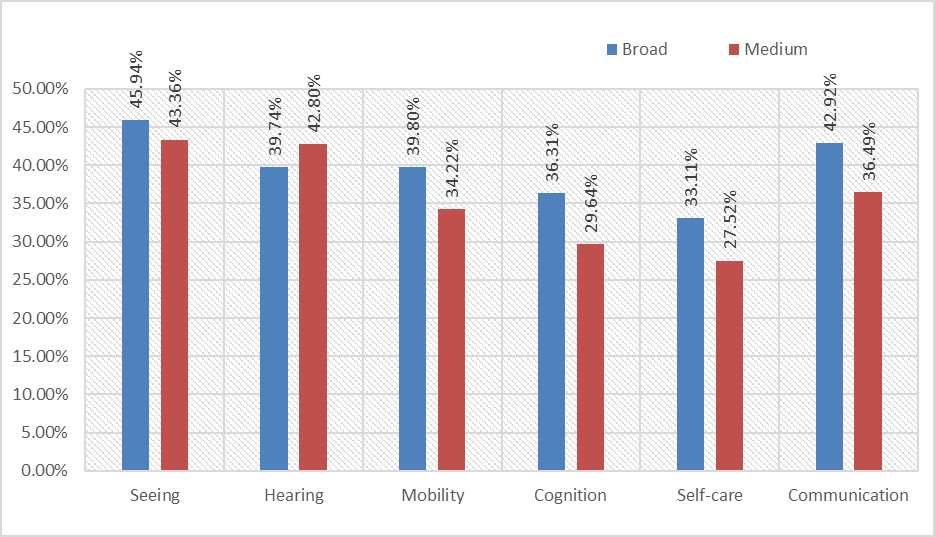

By looking closely at the results of severe disability across all socioeconomic characteristics, it can be noted that the deterrent impact of disability on employment becomes stronger as the degree of severity increases. Importantly, the employment-to-population ratios, according to disability domains, are considered. Figure 3 reveals a remarkable heterogeneity among persons with disabilities in employment according to disability domains. The employment-to-population ratio is the highest among individuals with any or a severe disability in vision (45.9 per cent and 43.4 per cent, respectively). Then, the next highest is among those who have any disability in communication (42.9 per cent), and those who have a severe disability in hearing (42.8 per cent). The lowest is among those with any or a severe disability in self-care (33.1 per cent and 27.5 per cent, respectively).

Figure 3. Percentages of persons with disabilities who are employed, by domain and level of severity

Source: Based on the authors’ calculations using ELMPS (2018).

For those who are employed, the study found that 18 per cent of the public sector workforce are persons with disabilities. Such a remarkably high percentage of persons with disabilities in this sector is likely the result of the older age profile of workers, since those who have acquired jobs in this sector are more likely to retain their jobs until retirement. These findings also may highlight the commitment by the public sector to employing people with disabilities.

|

|

Broad definition |

Medium definition |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Demographic and socioeconomic factors |

Persons without disabilities (Percentage) |

Persons with disabilities (Percentage) |

Persons without disabilities (Percentage) |

Persons with disabilities (Percentage) |

|

Overall |

44.3 |

44.2 |

44.4 |

38.1 |

|

Gender: Female Male |

|

|

|

|

|

16.46 |

20.36 |

17.1 |

17.2 |

|

|

72.6 |

71 |

72.6 |

63.1 |

|

|

Age groups: 15–19 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–64 |

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

14 |

14.2 |

7.9 |

|

|

37.6 |

43.8 |

38 |

37.6 |

|

|

55.2 |

51.4 |

54.7 |

59.3 |

|

|

61.6 |

58.5 |

61.3 |

54 |

|

|

58.9 |

48 |

56.9 |

37.9 |

|

|

26.4 |

19.9 |

25 |

12.3 |

|

|

Geographical location: Urban Rural |

|

|

|

|

|

44.2 |

42.9 |

44.3 |

35.4 |

|

|

44.3 |

45.4 |

44.5 |

40.6 |

|

|

Wealth quintiles: Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 |

|

|

|

|

|

45 |

43.5 |

44.9 |

41.4 |

|

|

44.9 |

41 |

44.7 |

34.6 |

|

|

43 |

45.1 |

43.4 |

38.1 |

|

|

44.6 |

44.7 |

44.9 |

36.7 |

|

|

43.9 |

46.5 |

44.4 |

39.4 |

|

|

Education: Illiterate Reads and writes Primary Preparatory General secondary Vocational secondary Tertiary |

|

|

|

|

|

39.6 |

32.4 |

38.7 |

25 |

|

|

55.9 |

47.8 |

54.2 |

56 |

|

|

37.3 |

39.2 |

37.5 |

38.8 |

|

|

24.7 |

36.3 |

25.8 |

33.2 |

|

|

17.9 |

28.6 |

18.9 |

23.7 |

|

|

52.4 |

54.4 |

52.7 |

47 |

|

|

60.7 |

64.1 |

61.2 |

60.5 |

|

Source: Calculated by the authors using ELMPS (2018).

[1] The ELMPS (2018) is the fourth wave which is publicly available upon request on the ERF website through the following link: http://www.erfdataportal.com/index.php/catalog/157.

[2] The differences were also tested using the chi-square test and the same results were obtained.

[3] According to this definition, if an individual worked in the last week for at least one hour as a wage worker, self-employed worker, employer or unpaid family worker, then he/she is considered employed. On the other hand, if an individual was willing to work, actively searched for an employment opportunity in the previous three months and was ready to start working in the next two weeks but could not work for an hour over the last week, then he/she is considered unemployed. An individual is in the labour force if he/she is employed or unemployed.

[4] The gap is not a sizeable one bearing in mind that other factors which can affect these ratios are not considered here.

[5] The sample size of the working-age individuals with complete disabilities is small (236), and this difference is not statistically significant using the chi-square test. So, we should be careful while interpreting its results.