Table of contents:

Coverage of Persons with Disabilities

Arriving at precise or comparable rates of social protection coverage for persons with disabilities in different contexts is highly challenging. For one thing, definitions of social protection measures as well as of disability differ between, and frequently within, countries, as will be discussed below. Furthermore, persons with disabilities may benefit from a social protection scheme by reason of, for example, being poor or old rather than because of their disability. This could mean that the statistics in fact underestimate the number of persons with disabilities who are covered. Another factor which risks undermining the validity and reliability, and thus the comparability, of the data on social protection coverage is that it is sometimes unclear whether it refers only to direct coverage, or whether it also includes indirect coverage, such as that enjoyed by the spouse or children of a formal worker.

To the extent that data on social protection coverage for persons with disabilities is available, it usually pertains only to specific schemes. Although such statistics can give an indication about the ability of particular programmes to include persons with disabilities, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the overall social protection coverage of persons with disabilities due to the fact that in most countries there exist more than one programme. Data on coverage of persons with disabilities is usually not available for all programmes, and some persons with disabilities may be covered by more than one.

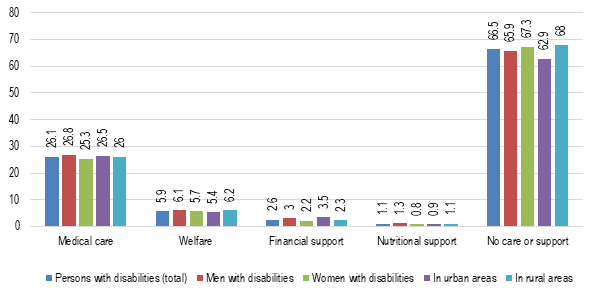

One of few examples from the Arab region of overall (rather than scheme-specific) coverage among persons with disabilities is included in Yemen’s 2013 National Health and Demographic Survey. The results, presented in figure 11, indicate that, at the time of the survey, 26.1 per cent of persons with disabilities had during the past year received medical care, 5.9 per cent “welfare”, 2.6 per cent financial support, and 1.1 nutritional support. 66.5 per cent, meanwhile, had received no care or support. Furthermore, men with disabilities were apparently covered to a higher degree than women with disabilities, even if the difference was not large. Similarly, persons with disabilities in urban areas were slightly more likely to be covered by some sort of social protection than those living in rural areas, though the latter group were more often covered by social protection in the form of “welfare” and nutritional support.

Interpreting these results, however, is not easy. For one thing, it is not entirely clear if the data pertains merely to disability specific types of social protection, or whether it also includes mainstream schemes,[1] nor whether it encompasses support given to other members of the household or only that given persons with disabilities themselves. Furthermore, it is difficult to know whether the data extends to social protection provided by actors other than the State, and what “welfare” for this purpose signifies. The survey does not present comparable data for persons without disabilities.

In many countries, various provisions of social protection for persons with disabilities are granted only to those who have a disability card (also referred to as disability ID). The proportion of persons with disabilities who have such cards could thus provide some indication of social protection coverage, though the specific provisions to which the cards grant access differ from country to country. Generally, having a card is necessary to access disability specific provisions.

In Lebanon, the disability card is the key to virtually all disability specific services provided by the State.[2] As of 2016, 97,735 persons in the country had disability cards. Of them, over 60 per cent were men.[3] The lack of other data on disability in Lebanon makes it difficult to extrapolate how big a proportion of persons with disabilities had cards, and whether (or to which extent) the gender discrepancy reflected the actual distribution of disability.[4] However, it may be noted that the number of card holders had increased by almost 25 per cent since 2013.[5]

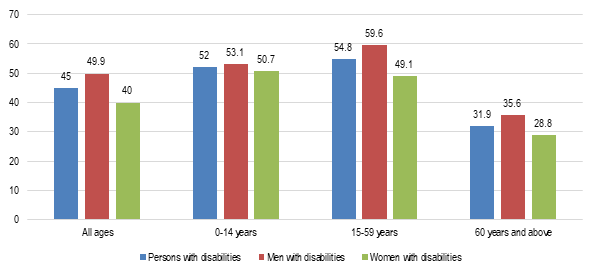

In Tunisia, the 2014 census found that only 45 per cent of persons with disabilities had a disability ID, and that there were considerable differences between men and women, and – in particular – between age groups (see figure 12).[6]

Figure 11. Percentage of persons with disabilities who received any kind of support for their disability in the past 12 months, Yemen, 2013

Source: Yemen, Ministry of Public Health and Population and Central Statistical Organization, 2015.

Figure 12. Percentage of persons with disabilities having disability cards, Tunisia, 2014

Source: Adapted from Tunisia, National Institute of Statistics, 2016b.

A study carried out by Handicap International, on the other hand, found that as many as 95 per cent of persons with disabilities in two selected areas of Tunisia used a disability card.[7] The large discrepancy between this finding and the one of the census might in part be due to the fact that respondents were for the purpose of the Handicap International study identified by the help of local disability organizations, which may have biased the selection towards disability card holders.[8] Furthermore, the two areas in which the study was carried out may not be representative of the country as a whole. Similar studies by Handicap International undertaken in areas of Algeria and Morocco found that the proportions of respondents who used a disability card were 100 and 50 per cent respectively.[9] It may be noted that in Morocco, this was the case even though the Moroccan disability card was not actually valid at the time of the survey, since the regulatory framework pertaining to it was being revised.[10]

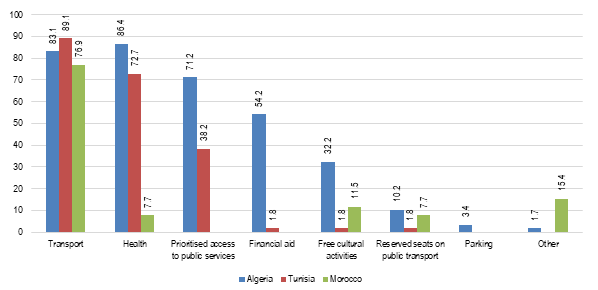

The Handicap International studies also asked respondents having disability cards for which purpose they used these. This is interesting since it gives an indication concerning the extent to which disability cards in practice grant access to social protection. As shown by figure 13, a large majority of disability card holders were in all three countries able to use the cards to access transport. In Algeria and Tunisia, furthermore, most respondents also reported that the cards allowed them to access health care. Only in Algeria, however, did it transpire that the disability card enabled a significant number of persons with disabilities to access financial aid. This is not surprizing, considering that Algeria, as mentioned above, has a disability specific CT programme called La Pension Handicapée à 100%.

Figure 13. Utilization of disability card by purpose, 2015

Sources: Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016a, p. 30; 2016b, p. 30; and 2016c, p. 31.

Since data on overall coverage of social protection is rare and imperfect, the remainder of this section will discuss coverage from the perspectives of specific social protection forms and schemes, focusing in turn on social insurance, social assistance and health care.

[1] The data is presented as “percentage of disabled people who received any kind of care and support for their disability” (emphasis added), which would seem to indicate that only disability-specific forms of social protection are intended. However, from the questionnaire itself it appears that the questions put to respondents was only whether they during the past year had “receive[d] any care or support”, which would seem to include mainstream as well as disability-specific form of social protection. See Yemen, 2015, pp. 206, 278.

[2] UNICEF, n.p., p. 12; Lebanon, Ministry of Social Affairs, 2016.

[3] UNICEF, n.p., p. 10.

[4] UNESCO, 2013, p. 11, suggests that the disability prevalence may be higher among men since “Lebanese males are more prone to acquire disabilities due to the wars and car and work related accidents as the number of workers and drivers is larger for males”.

[5] UNESCO, 2013, p. 9.

[6] “Tunis – 45% of disabled people hold disability card”, 2016.

[7] Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016a, p. 30.

[8] Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016a, p. 47.

[9] Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016b, p. 29; 2016c, p. 31.

[10] Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016c, pp. 26-27, 31, 36.