Table of contents:

Coverage of Health Care

Measuring coverage of health care systems is hardly easier than measuring coverage of social insurance or social assistance. This section focuses mainly on persons with disabilities’ coverage of health insurance. However, it should be recognized already at this stage that coverage of health insurance (whether contributory or not) is an imperfect proxy for access to health care. In some countries, as mentioned above, health care is provided freely to everyone, which reduces the relevance of having health insurance. Furthermore, even when persons with disabilities are covered by health insurance or live in contexts where health care is in theory free for all citizens, there may in practice be considerable problems regarding access and adequacy.

Out-of-pocket expenditure on health care is comparatively high in the region,[1] indicating that access often requires paying upfront. The fact that persons with disabilities, on the one hand, are disproportionately poor and, on the other hand, tend to face even higher costs of health care than persons without disabilities seems to imply that their ability to pay upfront for the care they need (or to purchase private insurance) is restricted.

The number of persons with disabilities benefiting from SHI should in most countries more or less mirror their social insurance coverage number, and therefore be low. In countries such as Jordan, where SHI has been freely extended to persons with disabilities, their coverage should theoretically be 100 per cent. However, the 2015 census indicated that around a third of Jordanians with disabilities were not covered.[2] The 2013 census in Sudan found that only 60 per cent of persons with disabilities had SHI.[3] In Egypt, the provision of free SHI for children with disabilities in practice applies only to children who are registered in school, implying that coverage is far from complete.[4]

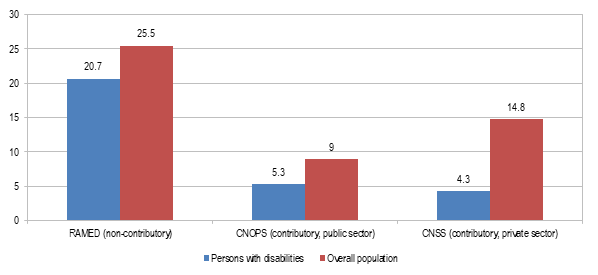

In Morocco, as shown by figure 16, only 5.3 per cent of persons with disabilities surveyed about their health insurance status indicated that they were – directly or indirectly – covered by the Caisse Nationale des Organismes de Prévoyance Sociale (CNOPS), the scheme for public sector workers, and 4.3 per cent that they were covered by the Caisse Nationale de Sécurité Sociale (CNSS), the scheme for private sector workers. Among the population as a whole, the corresponding rates were 9 and 14.8 per cent, respectively. These figures suggest that persons with disabilities are underrepresented among beneficiaries of both schemes, and that coverage through private sector employment is particularly inaccessible to them. The same survey also showed that 20.7 per cent of persons with disabilities benefitted from the non-contributory health insurance scheme RAMED. This would imply that they are underrepresented among RAMED beneficiaries as well, since the total number of such beneficiaries as of 2015 amounted to some 8.5 million – around a quarter of all Moroccans.[5]

Figure 16. Health insurance coverage (percentage) among persons with disabilities and the overall population, Morocco, 2013-2015

Source: Morocco, Ministry of Family, Solidarity, Equality and Social Development, 2014, p. 59; CNOPS, n.d.; CNSS, 2014, p. 40; and World Bank, 2015a, p. 25.

Note: Data on coverage among persons with disabilities is based on self-reporting, total coverage calculated on data from CNOPS, CNSS and World Bank. Comparisons presented should therefore be viewed as indicative.

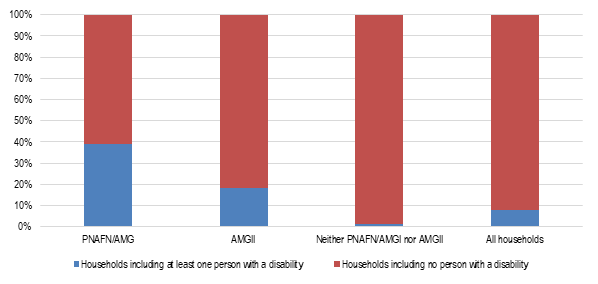

Figure 17. Households including at least one person with a disability as percentage of households covered by PNAFN/AMGI, by AMGII, by neither, and all households, Tunisia, 2014

Source: Center for Research and Social Studies (CRES) and African Development Bank, 2017, pp. 167, 179.

As mentioned above, 39.1 per cent of households benefiting from Tunisia’s PNFAN as of 2014 included at least one person with a disability. This can also be used as indicator of the extent to which persons with disabilities in that country were covered by the non-contributory health insurance programme AMGI, since it and the PNAFN share the same targeting mechanism (see further below) and beneficiary pool. Among the 588,199 Tunisian households benefiting from AMGII, which provides heavily subsidized health insurance, 18.2 per cent included at least one person with a disability.[6] As observed above, households with one or more persons with a disability constituted only 8.04 per cent of all households in Tunisia, meaning that such households were highly overrepresented among AMGII beneficiaries, though not to the same extent as among PNAFN/AMGI beneficiaries. It may further be observed that only 1.21 per cent of households which did not benefit from PNAFN/AMGI or from AMGII included one or more persons having a disability (see figure 17).[7]

Although it is difficult to compare the coverage rates for Morocco and Tunisia, primarily since they are based on different units of analysis (individuals/households) and since the definitions of disability used may diverge, it would appear that persons with disabilities in Tunisia are to a higher extent covered by health insurance than in Morocco. In addition, as shown by figure 18 further below, the surveys conducted by Handicap International and national disability organizations in Morocco and Tunisia have indicated that persons with disabilities in the former country to a much higher extent than in the latter consider access criteria to be a major concern. The discrepancy in terms of coverage of persons with disabilities may in large part be a result of the fact that disability, as will be elaborated upon below, is included in the targeting formula for PNAFN/AMGI.

In Lebanon, as noted above, the disability card should in theory grant persons with disabilities free health care. Reportedly, however, that is not the case in practice, as government hospitals frequently are reluctant to provide care to disability card holders. This has been attributed to the lack of funding allocated by the government to reimburse hospitals, and to the fact that “the [disability] card is not like insurance cards that are produced by insurance companies or the social security. Without being linked to any central information unit, the disability card does not provide either medical history or extents of coverage”.[8] Attempts to improve the collaboration between the Ministry of Social Affairs, which issues the disability cards, and the Ministry of Public Health have apparently not been fruitful,[9] though it was recently announced that the two will renew their efforts to ensure that persons with disabilities are guaranteed health care.[10]

These findings from Lebanon can be contrasted to those presented by Handicap International regarding Algeria and Tunisia. As shown above, a large proportion of disability card holders in those countries reported being able to use the cards to access health care. In Algeria, notably, this is the case even though the disability card in itself does not suffice to access care: persons with disabilities must first obtain the disability card, and secondly a so-called chifa-card, on which is registered data concerning the card holder’s identity and medical history.[11]

Importantly, data on the social protection coverage of persons with disabilities predisposes a definition of disability. The fact that definitions, as will be discussed in the next chapter, often vary between and within countries mean that data on coverage cannot easily be interpreted or compared. This indicates the importance not only of producing more data on the social protection coverage of persons with disabilities, but also of ensuring the quality of such data.

[2] Jordan, Department of Statistics, 2015.

[3] ESCWA, 2017c, p. 23; Stars of Hope Society, 2013, p. 49.

[4] Egypt, 2015; United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2010, p. 15.

[5] 3.8 percent of persons with disabilities, furthermore, reported being covered by other forms of insurance, including the private variety (0.7 percent) and ”professional” insurance (3.1 percent). It is not entirely sure what the latter signifies. Since no comparative rates are available for the population as a whole, coverage of this sort has not been included in the figure.

[6] Centre de Recherches et d'Etudes Sociales (CRES) and African Development Bank, 2017, pp. 167, 179.

[7] Ibid.

[8] UNESCO, 2013, pp. 13-14

[9] Ibid., p. 13.

[10] United Nations Economic and Social Council, 2016, p. 5.

[11] Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016b, p. 24; Algeria, La Caisse Nationale de Sécurité Sociale des Non-Salariés (CASNOS), 2014.