Table of contents:

Adequacy of Benefits and Services

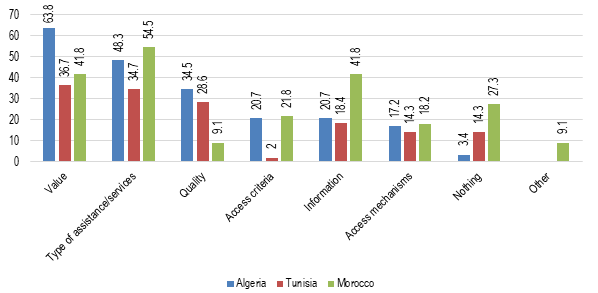

Even when monetary benefits are available and accessible, their small size frequently means that they do not suffice even to cover the added costs of disability. Since insurance-based disability pensions are typically calculated at least in part based on length of service and on the average or end-of-career salary, they are frequently lower for persons with disabilities than for old-age beneficiaries. In the State of Palestine, for example, the average disability benefit within the public sector social insurance scheme is 1,800 Israeli shekels, compared to 2,288 Israeli shekels for all social insurance benefits.[1] Within the framework of the studies carried out by Handicap International and national disability organizations in Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, persons with disabilities have stressed the low value of CTs as one of the biggest problems regarding social protection in their countries, as illustrated in figure 18.

Social assistance grants distributed within the framework of mainstream programmes are often fixed in size, meaning that persons with disabilities, despite the higher costs of living they typically face, receive the same sum as other beneficiaries. The PNCTP in the State of Palestine is an exception: there, the size of the CT is set based on a household’s poverty gap, calculated by means of the PMT formula (which, as noted, takes into account disability-related costs). Available data indicates that PNCTP beneficiary households which include persons with disabilities do indeed on average receive more generous grants.[2]

The inclusiveness of social protection is dependent, both directly and indirectly, upon whether social services are available, accessible and adequate. Extending health insurance to persons with disabilities is of limited utility if there are no hospitals or health clinics for them to use. The shortage of such facilities particularly affects persons with disabilities in rural areas and can undermine their access to other forms of social protection. For instance, this could be the case when the health clinics tasked with issuing the medical certificates used to determine disability status are not available or accessible.

Figure 18. Aspects of social protection requiring improvement according to persons with disabilities, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, 2015

Sources: Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016a, p. 35; 2016b, p. 35; and 2016c, p. 37.

Health care, even when available and accessible, is often of inadequate quality or otherwise not meeting the needs of persons with disabilities. For instance, persons with disabilities in a number of countries in the region have raised the issue of protheses and other forms of equipment being very expensive, of poor quality, or not available at all through the health care system.[3] The studies by Handicap International and disability organizations in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia indicate that persons with disabilities regard the type and the quality of services as among the most acute shortcomings relating to social protection, as shown by figure 18. Civil society organizations in the region have emphasized that women with disabilities are particularly affected by inadequate health-care systems, which often overlook their reproductive needs.[4]

Consequently, persons with disabilities, despite provisions in place to ensure their access to health care, often end up paying large sums of money for care and equipment, or not accessing it at all. Although CT beneficiaries in the State of Palestine benefit from free health insurance, a study in that country found that “the cost of expensive equipment or necessary medical supplies” often exceeds the value of the PNCTP grant.[5]

In Tunisia, as noted above, it appears that persons with disabilities are relatively well covered by the CT programme PNAFN and by the programmes providing free or heavily subsidized health insurance, AMGI and AMGII. However, a recent survey has indicated that 64 per cent of PNAFN/AMGI beneficiary households including at least one person with a disability face disability related expenses that are not covered by the program. For AMGII households including at least one person with a disability, the rate is 58 per cent.[6] The average non-reimbursed disability related costs for households benefiting from the PNAFN/AMGI or from AMGII and that include at least one person with a disability amount, respectively, to 54 dinars ($32) and 71 dinars ($42) per month and per person with a disability.[7] It should be noted that about five per cent of beneficiary households with at least one person with a disability benefiting either from PNAFN/AMGI or AMGII face non-reimbursed costs amounting to 200 dinars ($118) or more per person with a disability.[8]

The absence of education opportunities can critically impede persons with disabilities’ access to social protection – in the long term, since persons with low or no education are unlikely to find formal employment, but also in the more immediate term. This is exemplified by how children with disabilities in Egypt are excluded from social health insurance if they are not enrolled in school. Furthermore, as noted above, a number of countries in the region have made CTs conditional upon children’s’ school attendance, and other countries plan to do so. However, households can only fulfil such conditions if schools are available and accessible. This raises questions about whether households with children with disabilities risk not being able to access the CTs.[9] Certain schemes, such as the one in Morocco targeting widows,[10] have explicitly exempted children with disabilities from education-related conditions. Though this may in the short term be the most advisable approach, it risks reinforcing the perception that children with disabilities are not meant to go to school and thus perpetuate their exclusion.

[1] World Bank, 2016a, p. 59. The source does not specify a date for data. As of 2016, one Israeli shekel correponded to $3.9.

[2] Kaur and others, 2016, p. 59.

[3] See for Iraq, USAID, 2014, p. 25; for Morocco, Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016c, pp. 33-34; for Algeria, Pinto, Pinto and Cunha, 2016b, pp. 33-34.

[4] See, for example, Stars of Hope Society, 2013, pp. 48, 51; Information and Research Center and others, 2017, pp. 6, 11; Advocates for Human Rights & Mobilising for Rights Associates, 2017, pp. 15-16.

[5] Pereznieto and others, 2014, p. 29.

[6] Centre de Recherches et d'Etudes Sociales (CRES) and African Development Bank, 2017, p. 180.

[7] As noted earlier, the Tunisian national poverty line and extreme poverty line were in 2015 set to 1706 dinars and 1032 dinars per person and year, corresponding respectively to 142 dinars and 86 dinars per month.

[8] CRES and African Development Bank, 2017, pp. 180-181.

[9] For a general reference on disability and conditional cash transfers, see Mont, 2006.

[10] Morocco, Ministry of Family, Solidarity, Equality and Social Development, 2016b.